China is known for a lot of things, but their entertainment industry isn’t really one of them. Even within Asia, Korea and Japan tend to overshadow them.

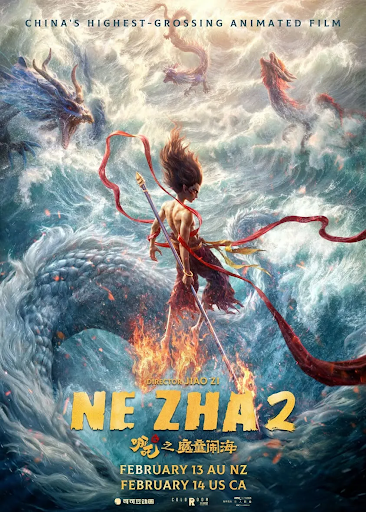

But China’s recent new movie “Ne Zha 2” has broken that lukewarm reputation and even challenged the global entertainment industry. In fact, “Ne Zha 2” is currently the highest-grossing animated film ever, earning over $2 billion in box office sales around the world [1].

The sequel to the 2019 film “Ne Zha,” “Ne Zha 2” is an animated retelling of Ne Zha, a god chronicled in a 16th-century Chinese novel known as the “Investiture of the Gods.” Despite technically reaching a god-like rank, Ne Zha is actually a demonic, adorably ugly 3 year old child. Don’t worry though—he has the maturity and mentality of someone much older, as he defends his family, befriends a dragon, and faces the evil villains of his world.

Set in a world loosely based on Chinese mythology, “Ne Zha 2” is a story about taking control of one’s own fate and challenging the rules of the world. In the very end “Ne Zha,” the prequel to “Ne Zha 2,” Ne Zha and Ao Bing—Ne Zha’s best friend whose original form is that of a dragon—sacrifice their physical bodies in order to save their families. The premise of “Ne Zha 2,” therefore, is their attempts at recovering their physical bodies while at the same time battling their world’s evil villains. In the very beginning of the movie, Ne Zha’s master successfully recreates Ne Zha’s physical body but fails to recreate Ao Bing’s. This prompts Ne Zha to go on a mission to Xu Tu palace, where he must pass multiple examinations and obstacles in order to obtain a magical elixir that will allow his best friend to regain his body. Aiding each other along the way, the more composed and sophisticated Ao Bing often takes control of Ne Zha’s body in order to help him pass these examinations. While they’re focused on saving each other, however, greedy villains wreck havoc on their world, forcing the two to take action.

The film’s gargantuan success alludes to China’s growing entertainment prowess. Indeed, the Chinese government has lauded the film as a display of China’s increasing cultural influence around the world. It’s also praised China’s growing independence: instead of relying on Hollywood to retell Chinese stories, such as in Mulan or the Kung Fu Panda franchise, “Ne Zha 2” is a signal that Chinese entertainers are now adept enough to tell their own stories without any foreign help [2].

Success and influence aside, however, a film review can’t be complete without some…personal opinion. I did go watch the film myself, but in a freezing-cold theater—according to the staff, the theater’s heaters had conveniently stopped working that particular day. Maybe that cold environment might explain my chilly views on “Ne Zha 2,” because despite its insane success, I honestly…didn’t enjoy it too much.

But still—its success obviously came from somewhere. For instance, if you’re an art or animation lover, you’re gonna love “Ne Zha 2.” The animation, the character design, the settings—they’re all so beautiful and exquisitely drawn. So many scenes from the movie still stick with me clearly in my mind: the Xu Tu palace, made completely of jade; the sky, ripped open like a canvas, lava and demonic dragons spilling out; and a massive, gnarly tree, perched with so many golden-robed fighters that they look like they’re the tree’s leaves…these are just some of the magnificent scenes from the movie.

But as a story? I thought it was…so disappointingly predictable. The character that most directly fits the trope of Most Likely to Be Killed to Advance the Plot—dies! The character that Seems Like the Good Guy But is Actually the Evil Mastermind All Along—is the evil mastermind after all! And the guy that Looks Mean But is Actually the Good Guy—turns out to really be the good guy under all that meanness!

Honestly, I thought the movie was a case of style over substance—a visual feast but a tepid story. As a Chinese-American fluent in Chinese, however, I might be a little biased—a review from Variety laments that “Ne Zha 2” is so full of Chinese mythology and Chinese wuxia concepts that the story is extremely difficult to grasp for non-Chinese audiences [3]. I, admittedly, didn’t have that problem, as I grew up with these stories and have been familiar with the original story of Ne Zha from a young age…but I definitely still see how accessibility is a large obstacle to the film. Just the names “Ne Zha” and “Ao Bing” are already barriers to a non-Chinese audience—from an English-speaking perspective, those groupings of letters are near impossible to figure out! (I’ll try to explain them, though: “Ne Zha” kind of sounds like “Nuh Ja,” and the “Ao” in “Ao Bing” sounds like something between “Ow” and “Oh.”). The honorifics the characters used to address each other—an element that isn’t really present in the much less status-obsessed societies of the English speaking world—were extremely complicated too, and made me question my Chinese fluency multiple times. Watching “Ne Zha 2” without having watched “Ne Zha” could also be a serious impediment to understanding and appreciating the movie.

That being said, however, the success of “Ne Zha 2” is greater than can be ignored. Just off of its box-office success alone, “Ne Zha 2” has already entered the gods’ pantheon of Chinese movies. But if China desires to make films that truly grip the world beyond the Chinese diaspora, there’s clearly still a lot of work to do.

Sources:

[1] https://screenrant.com/ne-zha-2-box-office-harry-potter-top-20-out-factoid/

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/10/business/china-box-office-ne-zha-2.html

[3] https://variety.com/2025/film/reviews/ne-zha-2-review-1236324922/