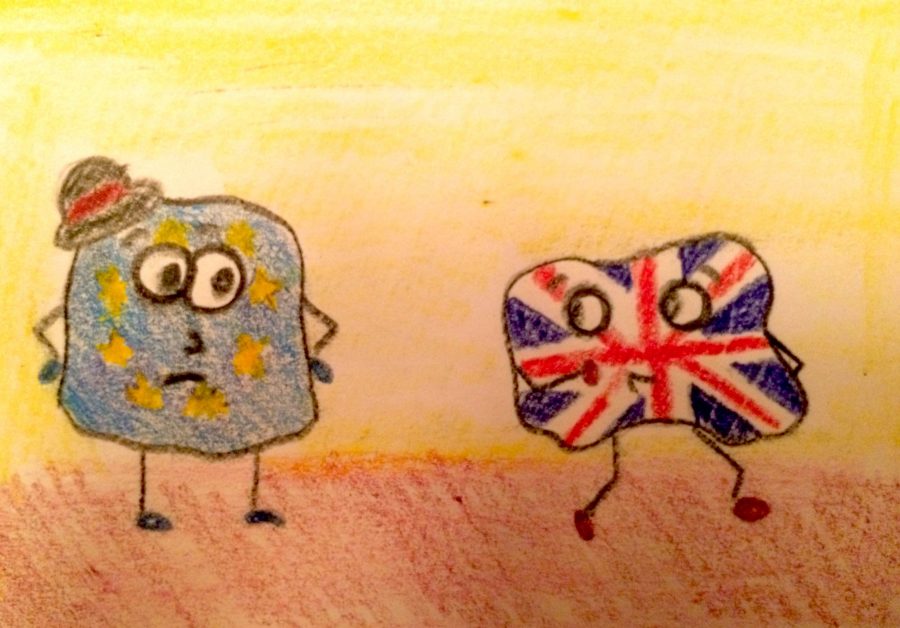

International Politics’ First Divorce

December 10, 2016

Despite the fact that all eyes are on the United States following Donald Trump’s election, it is important to stay attentive to what is happening in the United Kingdom, as the “Brexit” vote earlier this year has equally important international ramifications.

After 52 percent of the British population decided that they wanted to leave the European Union in June this year, Britain has been in a somewhat chaotic state. Former Prime Minister David Cameron, leader of the Conservative Party, was so distraught after the decision that he chose to resign in July. Theresa May, who had previously avoided the forefront of British politics, stepped into the spotlight as the country’s new Prime Minister to unite both sides of the political aisle in a turbulent time.

Leaders who had initially wanted the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, such as Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, shied away from the Prime Minister position, deciding that they would rather avoid the difficult task of finding a way to leave the EU without completely devastating the country economically.

Leaving the European Union causes a significant amount of issues for Britain. Being a member of the EU involves having “free movement” — both people and goods can move from country to country without any tariffs. When Britain leaves the European Union, they forfeit this benefit; Britain will have to use extra money and effort to continue trading with the rest of the European Union. As a result, the United Kingdom can expect overall trade to fall, as many businesses will avoid the new costs to trade. Even though Britain will not be able to leave until 2019 at the earliest, the “Brexit” is already having an impact on the economy. The value of the British pound has already fallen, and the average value of property has also fallen by £30,000.

Rohan Doshi ‘20 explains that “Brexit probably messed up Britain. Their economy is going to be in trouble.”

Despite opposition to the decision and potentially damaging consequences, the leaders of the UK must respect their population’s decision. Theresa May has told the population countless times that “Brexit means Brexit.” She promises to invoke Article 50, the legal process that separates a country wishing to leave the EU, by March 2017.

However, legal troubles stand in the way of the people’s will. The High Court — the British equivalent to the U.S. Supreme Court — found in early November that despite the referendum, the motion will still have to pass through Parliament.

“It’s a thorn in the side,” laments William Cui ‘17. “The governing body has to figure it all out before anything can actually happen.”

The main problem that plagues Theresa May is that legislators in London are going to meticulously pick out parts of the deal to negotiate and debate. In essence, they are creating the “Terms and Conditions” of Brexit. However, May would rather “keep it flexible,” as the political atmosphere in Europe continues to change. Much to May’s chagrin, this long and annoying process might push her March deadline back. At this point, it seems possible that the next United States presidential election might happen by the time Brexit actually occurs.

Although nothing has happened in Britain per se, much has already changed in the UK. Economic impacts aside, people are finding that they would rather stay in the EU than leave after seeing and hearing everything going on. Unfortunately, this realization comes too little too late. By 2019 or 2020, the world may regard Brexit as a mistake, but London will be too far into the separation process that they will be unable to turn back even if they so desired. Or perhaps Brexit will not happen, and the world will see stability return at the cost of a complete disregard for democracy. Nevertheless, British leaders will find no respite on the difficult road that has been laid out ahead of them.

The EU, for the most part, has agreed to cut off ties with Britain. EU leaders have previously told Britain that since it decided to file for divorce, there would be no turning back. There is no “still being friends” after this breakup.

Yet, the EU seems increasingly willing to compromise. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany said that the British might still be able to have free movement with the EU. However, this would set a bad precedent — if the UK can leave and still retain all the benefits, why can other countries not do the same? The EU might dissolve if countries follow Britain’s lead.

If the EU collapses, years of unity and cooperation as one collective Europe will go with it. The implications will be huge — the geopolitical equivalent of flipping a table with thirty thousand jigsaw pieces on it. In thirty years, analysts may look back to this British referendum as the catalyst that started downturn in Britain, and possibly even all of Europe.

Ryan Zhang • Dec 20, 2016 at 12:53 pm

I think this article really helps educate people on what is happening in other countries. It also explains it in a way that people can understand it and possibly relate to themselves. I think that we really need to educate ourselves on things going on in other countries than the U.S. and this article helps do so.